Achieving cradle-to-grave plant administration

An integrated system can take you through the four stages of a cabling system's life.

Jerry Owen / ISI

If we look closely at the life cycle of a structured cabling infrastructure, it is surprising to realize just how much cabling-system data is used and reused by different people for different purposes. This fact raises two points. First, if data is used again and again, the importance of its accuracy increases, as does its value. Second, if the same information is required for more than one process, a quick and reliable mechanism should exist to pass it from one user to another.

We are all familiar with the bits and pieces that make up a cabling installation, but in addition to cable and connectors, there is a great deal of information necessary to complete the picture. Commonalities exist within the data at each stage of a cabling-system's development, and these can be exploited for the benefit of all concerned.

Cabling is Darwinian

Cabling infrastructures evolve. As they advance from initial design, through construction, to additions and deletions over time, there is a cumulative growth of associated information. Everyone involved would benefit if this information database grew according to a defined, logical pattern.

Too often, the parties involved work independently, each with its own agenda and priority set, often isolated from the work of others. The result of this arrangement can be a duplication of effort and incompatibility of information, leading to unnecessary expense and reduced returns against effort.

As with any system, if you control what goes in, you can predict what will come out. By adopting a structured approach to the creation and use of data, you can control the content and flow of information from one stage to another. Therefore, you can create scenarios that maximize benefits by saving time and money, while providing mechanisms to effect quality control and compliance with standards.

Among other reasons, computers exist to support exactly this type of system, so it makes sense to use them to help us. Although many tasks associated with the design, recording, and management of cabling systems are already computerized, these facilities have generally been developed in isolation. So, while they may provide a short-term benefit in respect to a particular function, broader and greater collective benefits remain unattainable.

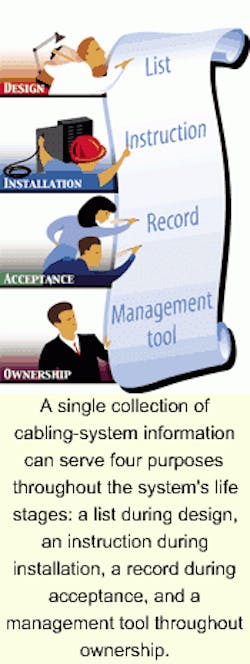

For the purposes of this discussion, I suggest that there are four distinct life stages of a cabling infrastructure:

- Design

- Build

- Acceptance/handover

- Ownership

We could add headings such as project management, procurement, and others, but these tasks logically fit within one or more of the four life-stage categories.

Design

Although some cable-management software packages offer facilities to assist at the design stage, they are generally restricted for use with a particular manufacturer's component set. Broadly speaking, cable-management systems traditionally focus on providing benefits for the system owner or administrator-a position we will consider when we reach stage 4 (ownership).

During the design process, a plan for physical layout is created, taking into account such considerations as numbers of cables, performance requirements, and environmental influences. Design efforts materialize as floor plans, accompanied by quantities of installation materials such as wall jacks, patch panels, cabinets, and cable boxes.

Imagine a system in which the designer records the final design in a convenient electronic database or spreadsheet format. "Not uncommon," you are likely to say. But how about in a format that is anticipated by the next group of professionals on the life-cycle list, even if that group includes an installation contractor with whom the designer has had no previous working relationship?

Build

The installer can use the information gathered during the design phase for a number of purposes, including cost estimation, procurement, build instruction, and testing. The installer can even use it to create the labels needed during installation. In short, the installation contractor can make a lot of use of this design-stage data. If he or she can anticipate the format and content of the data provided, the installer can establish and streamline operations accordingly.

For example, if the information is used with a parts database, the installer might import relevant sections directly into a bill-of-materials utility that would not only provide costing information, but could also automate the whole parts-ordering process. Other information might allow the installation contractor to identify the best way to use labor by ensuring optimum workflow.

Many contractors I speak with cite labeling as the bane of most jobs, partly because generating the number-sequence data is a time-consuming process. Not only would it be easy to generate labels from data supplied directly by the designer, but also the installer could produce the labels in advance.

I have seen many installations in which labels are created, then applied after the installation is complete. Accepting that this scenario is sometimes dictated by external factors; quite often it is simply that label printing takes a lower priority than cable pulling. Ultimately, this approach results in an unnecessary revisit to the jobsite for the sole purpose of applying labels.

One way or another, computers are already performing many of these operations. But by working within an organized, structured system, you can considerably increase efficiency. Furthermore, once you have established this system, you can monitor and improve on it to realize even greater benefits.

During a typical buildout, the installer adds data that includes cable-test results, installed cable lengths, and other comments. The installer might also record any modifications to the initial design that were made during the installation process. All of this information could easily be recorded in the designated format.

Acceptance/handover

Our imaginary database, originated by the designer, now contains all the information associated with as-built documentation that is normally required to fulfill warranty and sign-off requirements.

We can already see how to increase the efficiency with which information is passed from one function group to the next. If this information is presented in an established format, not only is the process streamlined, but also the presentation of the information is consistent. In such a scenario, the information and processes are the same; only the content actually changes from job to job.

The acceptance process inevitably includes the handover of some kind of documentation. Frequently, three parties are involved: the end user, installer, and warranty provider.

The least expensive and most convenient way to effect acceptance is for each party to receive a copy of the as-built documentation as a record of the cable plant's status in its current state. If these records are computerized, the parties can easily restrict the ability to change them. This fact is of particular value to the warranty provider, who may want to demonstrate the status of the installed cabling system in the future.

Ownership

Following acceptance, the infrastructure is put to use in the stage known as ownership-the final and by far the longest stage of the process.

Other than physical aspects of ownership, such as performance and availability, information like patching records and usage details primarily interest cable-plant managers. These records and details become an intrinsic part of the ongoing move, add, and change (MAC) process, which is traditionally seen as the main function of a cable-management system. Because this information is really an electronic record of the installation, the cable-plant manager can make inquiries of, and produce reports from, the data.

Information flow

Examining the model described above, you can identify and summarize points at which information is created, used, and modified. This is how it might work:

- The designer creates lists detailing the quantity of jacks, patch panels, cabinets, cable, and other system components, as well as the physical locations where these components will be installed.

- This designer passes this information to the installation contractor, who can use it to formulate a bill of materials, including costs, used to generate a bid. Once awarded the work, the contractor uses the same data to aid the purchase of materials, organize workflow, and produce build instructions. The contractor also uses the same data to monitor progress of the installation, create a testing schedule, and produce labels. Finally, technicians append test results to the individual cable records to provide a comprehensive handover package.

- All parties involved in the acceptance of the installation now have an accurate record of the cable plant's status, complete with details of all the hardware used, where everything is, and what is connected to what. This record serves as a mechanism for the contract-completion agreement, release of funds, and perhaps issuance of the warranty.

- From this point on, the information can form the basis of a computer-based cable-management strategy for recording MACs and other system-status changes for the benefit of the cable-plant administrator.

The case for the end user to implement an effective cable-management strategy is well-documented. But the adoption of a system that forces order over the entire evolutionary process of a cabling infrastructure can offer far wider benefits that equate to greater efficiency and lower costs.

A spin-off benefit of this approach is the ease with which the end user can comply with standards-particularly the TIA/EIA-606 standard covering cable-plant administration.

A cable-management system that addresses all the functions described in this article will reduce the time spent performing the same, non-revenue-generating tasks required for every cabling installation. It would create as-built documentation faster than any other method, while ensuring record-quality consistency and standard-compliance.

A system like this will also benefit the installation contractor, by saving time and helping automate the documentation process. Most cabling installations are similar, and although different contractors may employ different business methods, many processes and tasks are repetitive and common to each job. The range of benefits that a sophisticated cable-management system offers could be realized from as early as the design and initial-bid stage, all the way through acceptance and sign-off, and onto the useful life of a cabling system.

Jerry Owen is national cabling product manager for ISI's (Schaumburg, IL) Infortel-Cable Management System.